The Legend of Lincoln Mill

Hurricane Ida Flood

The Lincoln Mill opened in 1860 and was one of Manayunk’s numerous textile mills. In March 2021, the mill was purchased by a local developer, who began renovations on the building.

On September 2, 2021, Hurricane Ida struck Philadelphia and flooded the mill to historic water levels. The flood damaged the mill’s interior and revealed a hidden chamber in the basement. Human remains were found and a dark truth was discovered about the mill’s past.

Construction has since been halted and the mill is under investigation.

The Hidden Chamber

In the heart of Manayunk, perched along the banks of the Schuylkill River, stood the Lincoln Mill, a relic of Philadelphia’s textile boom. Beneath its stone façade and machinery, a darker story unraveled, one buried beneath layers of secrecy.

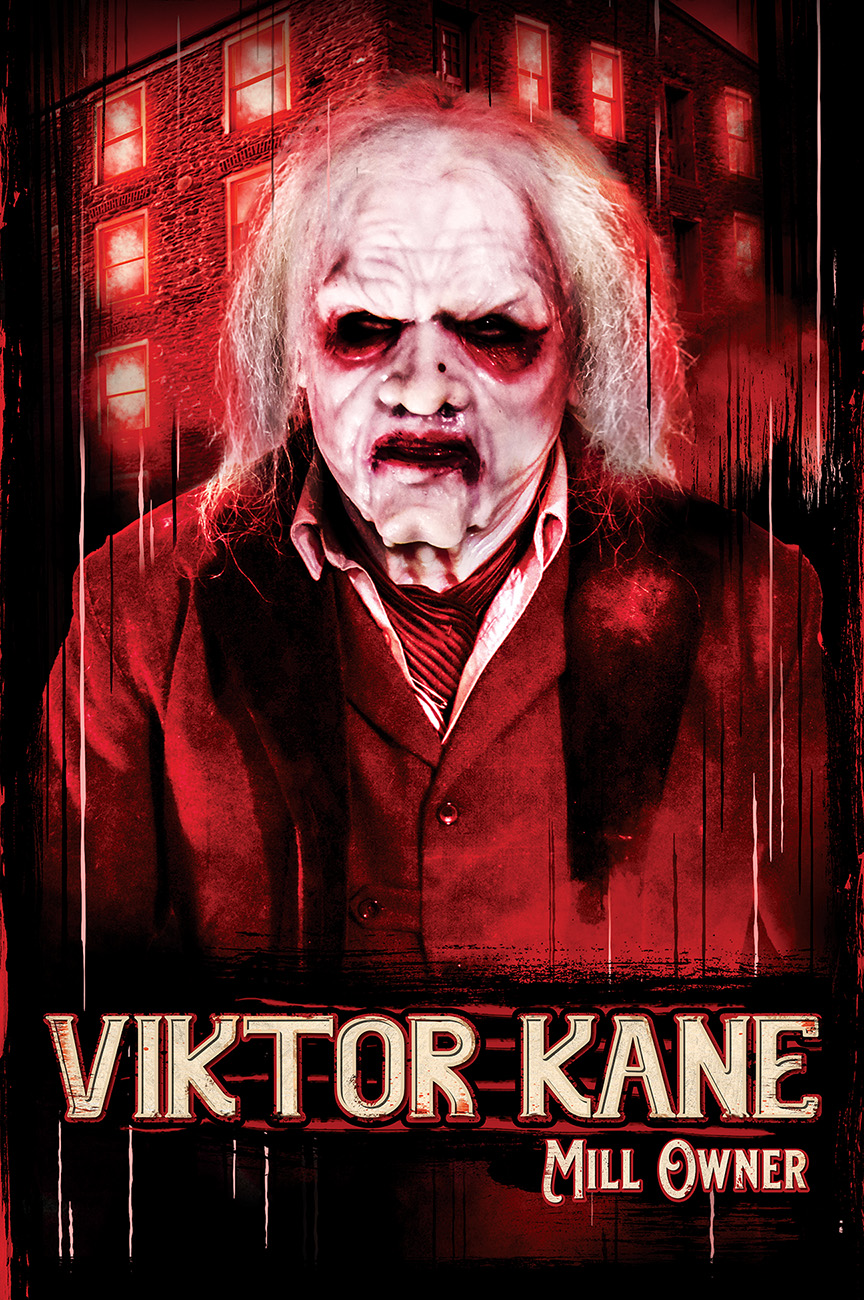

Viktor Kane, the mill’s enigmatic owner, was an eccentric industrialist. To outsiders, he appeared to be a forward-thinking businessman—one willing to embrace new ideas to keep the textile industry alive during its darkest years.

Viktor Kane was selected to implement a new workforce initiative designed to stabilize employment during a time of economic collapse. Backed by outside authorities and framed as a recovery effort, the program promised to keep mills operating, workers employed, and production steady when failure seemed inevitable.

The initiative was called the Labor Efficiency Program.

On the surface, it was a system of monitoring and optimizing worker output—tracking fatigue, injuries, and productivity to reduce downtime and prevent layoffs. Laborers who faltered, those who became ill, injured, resisted instruction, or simply slowed with exhaustion were flagged. They were quietly removed from the mill floor under the pretense of medical care and escorted to the infirmary first-aid area in the basement.

That infirmary was where science and horror entwined. Under Kane’s orders, faltered workers were subjected to injections of serums and tonics, concocted to sharpen reflexes, deaden pain, and strip away fear. But the drugs did more than enhance performance, they dissolved identity. Those who survived the injections returned to the mill floor, hollow-eyed and obedient, moving in mechanical unison like puppets on invisible strings.

When the side effects became too severe; causing seizures, hallucinations, or complete psychological breakdown, the workers were taken deeper in the basement.

Hidden beyond the infirmary, the Chamber was a grotesque theater of suffering, where subjects were closely observed and documented—each test designed to answer a single question: how much can a person endure before they break. Those who finally succumbed to the torment were disposed of.

The Program

Unknown to the public, the Labor Efficiency Program was not solely Viktor Kane’s creation. It was funded through a federal workforce initiative run by a little-known government agency charged with stabilizing employment during the economic crisis. Publicly, the program promised jobs, productivity, and industrial recovery. Privately, laborers were treated as test subjects in a study of human endurance and compliance.

The operation extended far beyond Lincoln Mill. Workers from across Manayunk—those injured, indebted, undocumented, or easily silenced—were quietly redirected to the Lincoln Mill. Through official permissions and concealed passages beneath the mill, Lincoln Mill became the center of a covert human experimentation program. What was justified as recovery was, in truth, control.

The Workforce

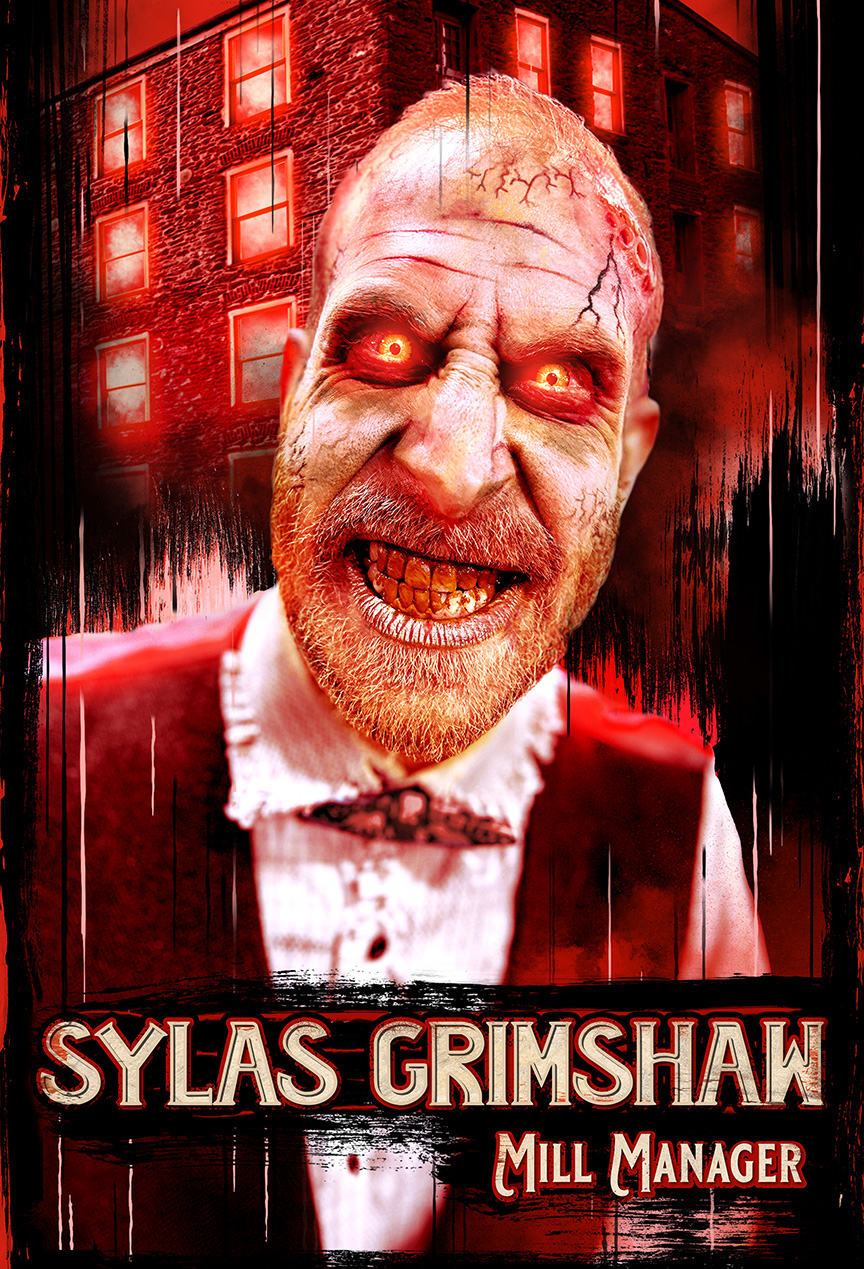

Sylas Grimshaw, the mill manager, enforced the daily operations with brutal efficiency. He kept the laborers in line, pushing them harder each day, tracking performance, and identifying “candidates” for the Program. He was Kane’s right hand man—cold, calculating, and without mercy.

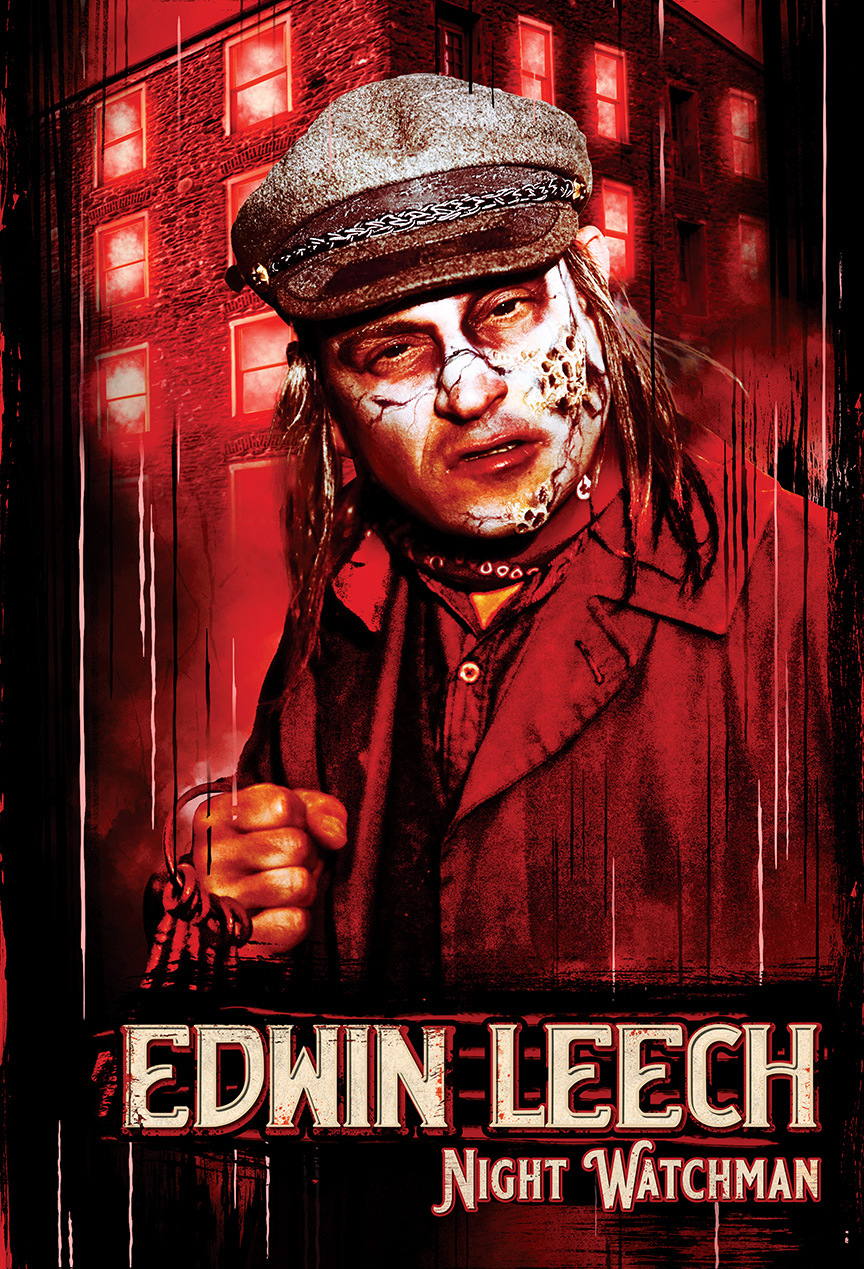

The Mill’s night watchman, Edwin Leech, patrolled the grounds with a lantern in hand. He guarded the infirmary and the Chamber entrance.

And then there was Gretchen, the seamstress. Sweet and motherly on the outside, she had once designed safety uniforms for the workers. But as the experiments grew more extreme, she was tasked with something far more morbid: shaping and stitching the test subjects into more “useful” forms.

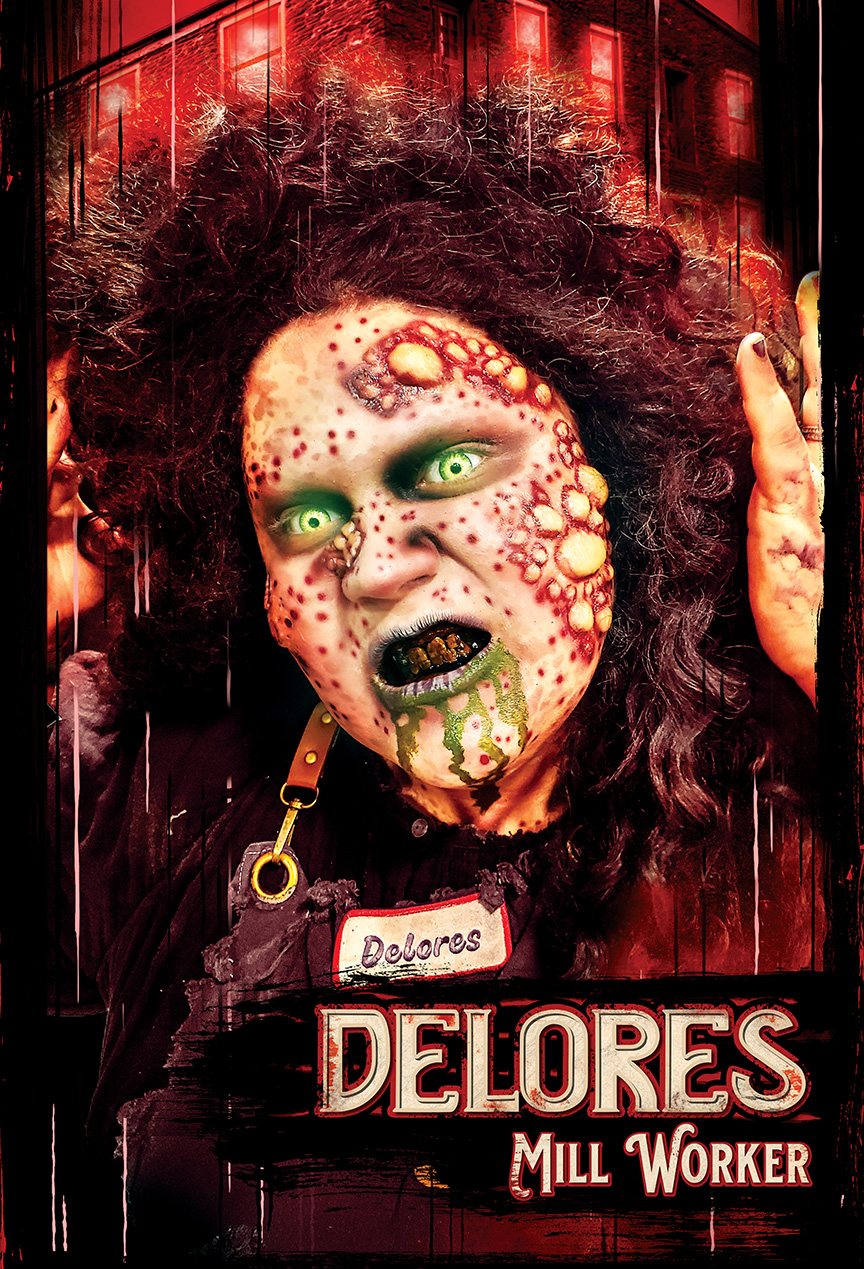

Among the weary faces on the factory floor was Delores, an ordinary mill worker who carried herself with quiet humility. She befriended many of her fellow laborers, offering small kindnesses and listening ears. But in truth, Delores was working in secret for Sylas. If any worker began to complain, question the methods, or show signs of suspicion toward Viktor’s operation, she would quietly betray them—her warmth a mask for her treachery. She was the net that caught those slipping through Sylas’s grip.

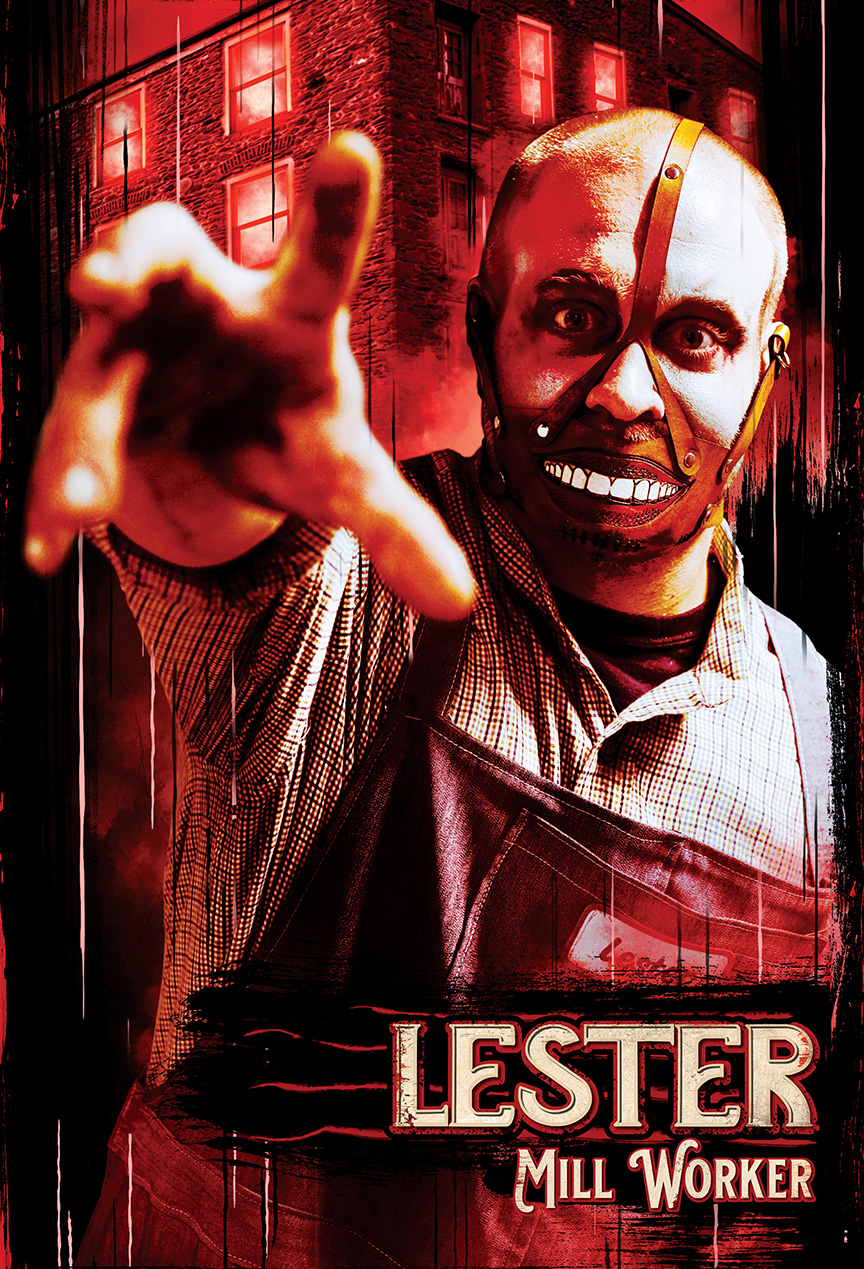

It was Mildred and Lester, longtime hands at the mill, who first began to sense that something was terribly wrong. As they unraveled fragments of Viktor’s plan—pieces of machinery that didn’t make sense, schedules that grew more punishing, whispers of workers disappearing—they grew increasingly paranoid. Their distrust set them apart, making them targets of both Sylas’s gaze and Delores’s quiet watchfulness.

By the late 1930s, the Mill’s output had doubled. No one questioned how. But the townsfolk noticed that families of missing workers never found closure. The few who investigated too deeply—journalists, union organizers, curious neighbors—also vanished. The operation was kept a secret throughout the 1930s.

To this day, the Lincoln Mill remains haunted—not just by the ghost of Viktor Kane and his tortured workers, but by the legacy of what was done there. Visitors claim to hear whispers behind the walls, footsteps echoing in the dark, and the soft creak of chains swinging just out of sight. And in the stillness of night, if you listen closely enough, you might just hear them: the forgotten workers of the Lincoln Mill, still dancing on their strings. Waiting to be set free.